Sometimes you read an excerpt of a memoir about adultery, and you think, Huh. That’s an interesting structure for a book. So you buy the book and you read it. Then you remember that you have another memoir about adultery somewhere in one of the stacks on your dining table that your husband keeps gently reminding you to remove so that the family can once again eat together, should you all happen to be at home and hungry at the same time. So you pull that book out of the stack, feeling virtuous because the stack got smaller! What a wonderful wife you are! You read that book. Then you happen to have coffee with your agent because she’s reviewed the first part of the novel you’re working on, and, in a surprise twist, she wants you to add an infidelity subplot. You don’t know anything about infidelity firsthand (see above, the part about being a wonderful wife). You are, however, a pro at reading about infidelity. You’re already two books in! You’re delighted to read more! This is how you find yourself writing a newsletter all about cheating.

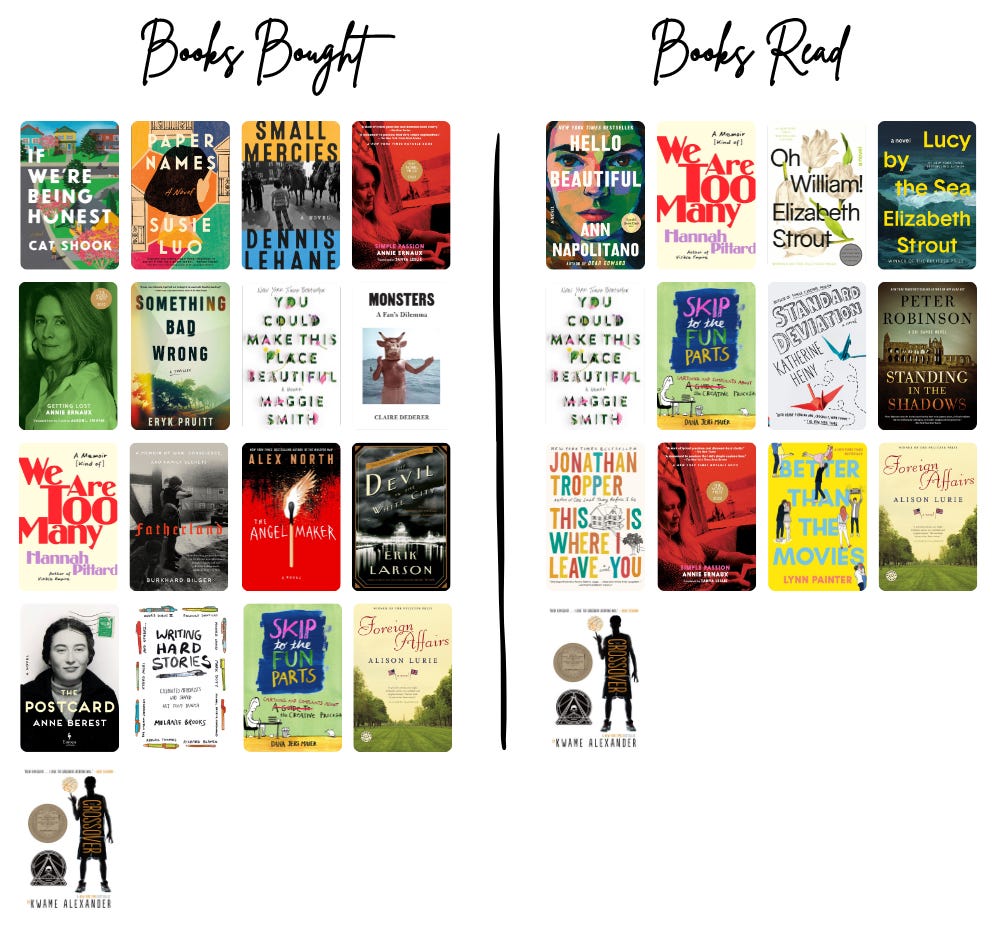

First, the book with the intriguing structure: After Hannah Pittard learned that her husband was having an affair with her best friend, she divorced him and started “writing down the conversations … that were just echoing, echoing, echoing” in her head.* These conversations, which read like scripts of a play, became the first sixty percent of her latest book, We Are Too Many: A Memoir [Kind of]. “Sometimes they are imagined from whole cloth,” she says in the book’s introduction, “(as when I attempt to reconstruct the discussion between my husband and best friend that might have led to their initial infidelity), and sometimes they are recalled as clearly and honestly as if they’d taken place just last night (as when my husband suggested we have a baby in order to curb our excessive drinking habits).”

I wanted to love a book overflowing with dialogue, primarily because I enjoy writing dialogue. But it’s hard enough bringing people to life on the page with dialogue plus description and thoughts and actions and reactions and backstory. Dialogue alone felt interesting but incomplete. By the time I reached the later sections of We Are Too Many, I didn’t feel invested in anyone. But the book moves quickly, and if you’re curious about varying forms of storytelling, it’s worth a read.

Next, the book in the stack on my table: You Could Make This Place Beautiful, a memoir by Maggie Smith about the end of her marriage following her husband’s infidelity. Ann Patchett, one of my favorite authors, sent this memoir to me as a surprise treat. You, too, can receive monthly a book selected by Ann and her team at Parnassus, the bookstore she owns in Nashville, if you sign up for the store’s First Editions Club. You’ll have no idea what book they’re picking and—my favorite part of all—each selection arrives with a note, often (though not always) from Ann. In the page-long note that accompanied You Could Make This Place Beautiful, for example, Ann wrote, “Take a good look at the cover. Isn’t it beautiful? That’s how beautiful the whole book is. That’s how many secret doors it opens. Forget about expectations, just turn the page and step inside.”

Do Ann and I always fully agree? Of course not. We’re soulmates, not the exact same person.** In my view You Could Make This Place Beautiful is a powerful book, but it’s a bit too long; and the structure and voice sometimes feel forced. Isn’t that part of the pleasure of a book recommendation from a trusted source, though—figuring out in what ways your views diverge, and why? (It’s also dawning on me that my standards might be impossibly high.)

I do wholeheartedly love Katherine Heiny’s Standard Deviation, one of the books my agent suggested I read as I move forward with my novel. It tells the story of a man who leaves his first wife, Elspeth, to marry his then-girlfriend, Audra, only to be drawn back into an unexpected connection with Elspeth, partly at the urging of Audra. Talk about full-fledged, memorable characters! I’m trying to select a passage to illustrate this, but I’m having trouble because there are too many great examples. I’m going with the very first two paragraphs of the book:

It had begun to seem to Graham, in this, the twelfth year of his second marriage, that he and his wife lived in parallel universes. And worse, it seemed his universe was lonely and arid, and hers was densely populated with armies of friends and acquaintances and other people he did not know.

Here they were grocery shopping in Fairway on a Saturday morning, a normal married thing to do together—although, Graham could not help noticing, they were not doing it together. His wife, Audra, spent almost the whole time talking to people she knew—it was like accompanying a visiting dignitary of some sort, or maybe a presidential hopeful—while he did the normal shopping.

Don’t you instantly want to know more about Audra, and Graham, and how they ended up together, and whether they’ll stay together? Just from those mundane, Fairway details. It gets better, too. Wait til you read about Audra in the checkout line, mere pages later. I’ll never forget Audra in the checkout line.

I’m having a sense of déjà vu because my last post featured grocery store stories. It also included a relevant book by Annie Ernaux, and now I’m going to tell you about an infidelity book by Annie Ernaux. It’s possible every newsletter I ever write will contain something about Annie Ernaux, because, good lord, can that woman write. Simple Passion is an account of her affair with a married man. Take a look at just this one paragraph:

From September last year, I did nothing else but wait for a man: for him to call me and come round to my place. I would go to the supermarket, the cinema, take my clothes to the dry cleaner’s, read books, and mark essays. I behaved exactly the same way as before, but without the long-standing familiarity of these actions I would have found it impossible to do so, except at the cost of a tremendous effort. It was when I spoke that I realized I was acting instinctively. ... The only actions involving willpower, desire, and what I take to be human intelligence (planning, weighing the pros and cons, assessing the consequences) were all related to this man: reading newspaper articles about his country (he was a foreigner) choosing clothes and make-up writing letters to him changing the sheets on the bed and arranging flowers in the bedroom jotting down something that might interest him, to tell him next time we met buying whisky, fruit, and various delicacies for our evening together imagining in which room we would make love when he arrived. ... I had no future other than the telephone call fixing our next appointment.

Do you see the precision of the details, the focus on the body and mind and their interplay, the interest in what’s often considered taboo and female, the voice that’s startlingly personal but also clinical? That’s all signature Ernaux. The brevity, too—Simple Passion is only 80 pages long. But it yanks from the air a fundamental aspect of humanity—the effects of desire—and holds it in a tight fist on the page.

I’m going to try to do as my agent suggests and write about infidelity myself now. I’ve also decided to let S. A. Cosby’s selections in this By the Book interview guide my reading for a while. It’s already proving an immensely rewarding choice—highly recommended—I’ll tell you all about it soon.

Faithfully yours,

Julie

* From Hannah’s interview on the Otherppl podcast.

**You might be thinking, You can’t be soulmates with someone who’s never heard of you, Julie. In response, I say to you: Are the workings of the universe not manifold and wondrous and frequently beyond our ken?

Darn! These quotations make me want to read more books! 😳😅🤷♀️ Delightful post.

I can tell from your adoration of these writers and each gorgeously constructed sentence that your own writing on infidelity will be quoted by others in much the same way.